We’ve curated our best editorial secrets and industry insights into a series of articles. They range from getting started through staying on track and grasping the publishing business. Put those fuzzy slippers on your feet, pull up a cushy armchair, and enjoy.

Creating a Series Grid From Scratch

Finish Your Book in Three Drafts (3D), the third book in the Book Architecture trilogy, came accompanied by a wealth of writing know-how in the form of 9 bonus PDFs. Behold, PDF #4.

Finish Your Book in Three Drafts (3D) lists a lot of good reasons to make a series grid:

• You can see your series repetitions and variations clearly

• You can identify or create foreshadowing

• You can use it to see plot holes immediately

• It can help orchestrate your pacing as suspense, surprise, or shock

• It is holistic and thus points out lateral connections with other series

To demonstrate how to create a series grid from scratch, I could have chosen an unpublished work of my own that no one would know. Or I could have chosen something that most people would have read, even if it was a while ago—something like The Great Gatsby, which we used in chapter four of 3D.

But creating a series grid is an act of love, so I chose Franz Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis, my favorite work of literature. If you read chapter seven of Book Architecture (BA), you can see the full grid I put together for Kafka’s work as well as a synopsis of the story to refresh your memory. For our purposes here, however, you won’t need any of that, because the point is you don’t necessarily have to have superior tools or insight before you get started on something like this. That’s why we initially do it in pencil.

You already know from the “Cut Up Your Scenes” section in chapter three of 3D that I recommend hands-on work. Getting into the material by constructing a physical series grid slows you down and forces you to think more closely about each of the choices that brought about a particular story.

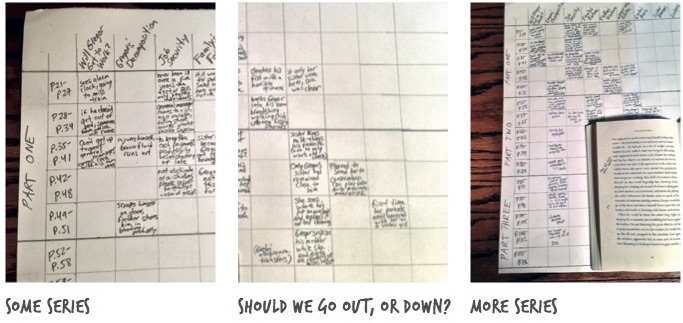

Setting Up the Rows: Kafka’s Scenes

When we are setting up the rows, the easiest way to keep track at first is by noting the divisions the author has given us. In this case, The Metamorphosis is divided into three parts. Kafka weighted each of the parts almost exactly the same; each is between 31 and 34 pages long. Therefore, I think it is easiest to create the individual rows on the grid by simply dividing each part into five batches of about seven pages each. In the translation I am using (Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis. Trans. Susan Bernofsky. New York: W.W. Norton, 2014) the story is 98 pages long, so that’s 15 rows (p. 21–27, where the novella starts, is Row 1; p. 28–34 is Row 2, etc.).

I could also have broken up the story by scene name, which you might want to do if your work-in-progress isn’t far enough evolved to have a final order of chapters. When in doubt, break up the narrative by page numbers to simplify what can be a pretty dense process.

Setting Up the Columns: Kafka’s Series

Setting up the rows either by batches of pages or scenes—that was the easy part. How do we divide the columns? How do we choose our series? Recall that the easiest way to discover your series is simply to keep track of what repeats (an object, a person, a place, a phrase, or a relationship) and how it varies. You can pay special attention to the elements that repeat the most and/or that repeat when other series do (i.e., in key scenes and other critical moments).

In the first two columns, I put the two series of the novella that ask the most basic questions: Will Gregor Get to Work? and Gregor’s Decomposition (i.e., Is this the end of Gregor?). These questions relate to the “plot” most closely and ask the most visceral or immediate questions.

In the third column, I have charted a series entitled Job Security. In some ways, this series is the natural extension of Will Gregor Get to Work? because it lets us know what will happen if Gregor doesn’t get to work. It’s tempting to go for something bigger than Job Security, something like Hierarchy or even The Individual and the Collective. But if we are going to show—rather than tell—then a series needs to embody something sensual we can demonstrate to a reader, and which a reader, in turn, can track. Something like: Gregor hasn’t been ill once in five years, yet the first day he is even a few minutes late, the general manager shows up at his door. That doesn’t bode well.

I have put the series about Gregor’s Family’s Fortune in column four, taking my cue as to the importance of this series from the fact that there are so many iterations of it (out of a possible 15 rows, this column is filled with an event or detail 12 times). In the next column, I placed Father’s Violence. It isn’t that Gregor’s father appears so often—it is more a case of where he appears. Gregor’s father is a person who becomes a character through well-timed (and violent) iterations, at the end of both Part I and Part II.

The next column is a relationship that becomes a dynamic through repetition and variation. The Gregor and Grete series shows the relationship of these siblings changing from compassion and interdependence to increasing irritation and desperation on the part of Grete, until she deserts Gregor (and then returns to him in a bittersweet coda).

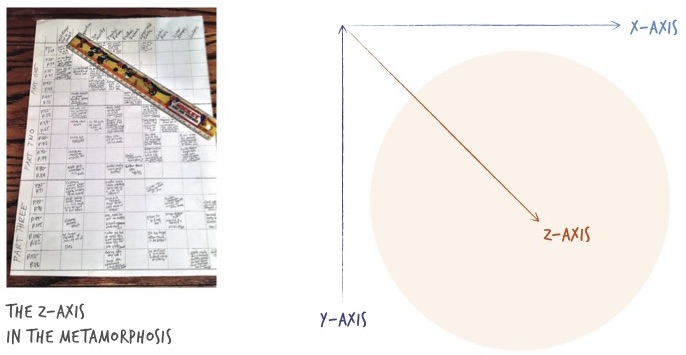

The Z-Axis

On the series grid, I chose to chart three more series: Grete’s Music, a character trait of Gregor’s sister which shows her culture and hence her desirability in the society of the time; Sister Emerges, the arc that traces the evolution of Gregor’s sister from “useless girl” to hard-won self-assurance; and the Lodgers, those intruders who room with Gregor’s family when the money gets tight. I could have chosen others: which Doors are locked, whether the Key is on the inside or the outside, Gregor’s mother’s Escapist Tendencies… you get the picture.

The series I have chosen to chart are what I believe to be the first nine in the top-down order of importance. How did I assess this? These nine series make sure that the story’s questions are never all answered at the same time; they push the action forward. What emerges is an interesting phenomenon. As you may recall from high school geometry, the vertical rows on a series grid—what we have here as a succession of seven-page batches of the story—is called the y-axis. The x-axis is the one that stretches out hori- zontally to include the nine series.

Why am I telling you this? Because following the logic that a series worth tracking has to ask a question and that, when one question is answered, another series has to ask a different one, there then exists a z-axis in addition to the x–axis and y-axis. is is actually a thing. If the x-axis is the width and the y-axis is the height, then the z-axis is the depth. On our series grid, it looks like this:

The z-axis, or the diagonal line marked by the ruler, shows how newly occurring series keep the story moving. One thing leads to another, or in the words of my colleague Renee: “Bazinga! I knew it. The diagonals had it the whole time. So, this begs the question: Do I start reconstructing important series in order to augment the diagonal? And if so, then how?”

Well, drawing a series grid is a good start. In the case of the series grid we have created for Kafka’s novella, the last point on our z-axis—that is, the farthest out on the x-axis and the farthest down on the y-axis—is the series where Gregor’s Sister Emerges. This is where the diagonal push and pull of the series grid comes to its culmination; our awareness of this is helped by the fact that the last iteration of this series is literally the last line of the book. Having disposed of Gregor and taken the day off, the family boards a tram for the country. At the end of the ride, Gregor’s sister—far from being a useless girl now—is the most energized family member when she “swiftly sprang to her feet and stretched her young body” (p. 118).

My hope is that by watching me craft an extended series grid, which is covered in smudge marks and mistakes when you look up close, you will have gained some confidence that you can do the same. You can, if you simply focus your attention on the necessary details, where, it turns out, the solutions are to be found as well.