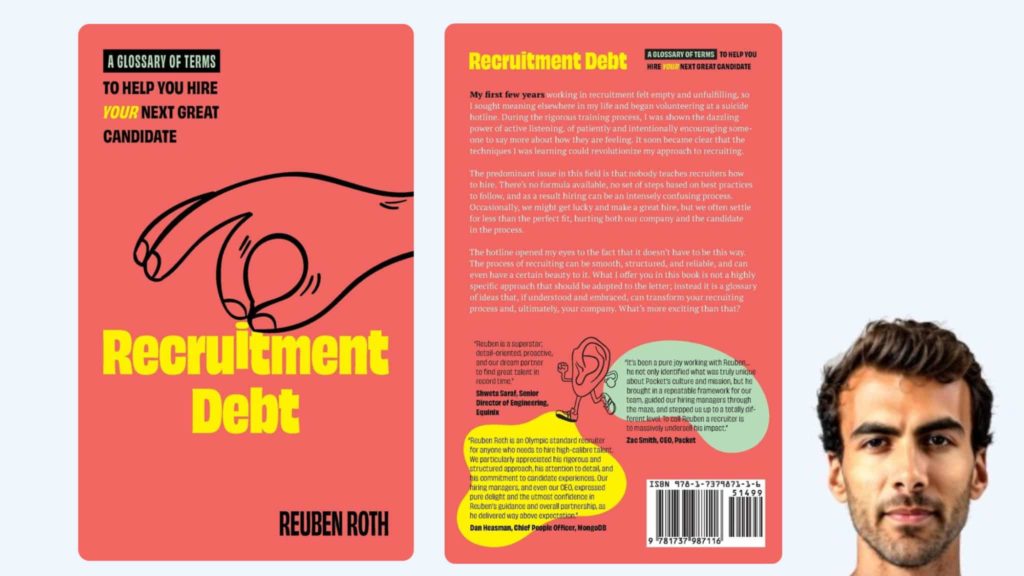

Madison Utley speaks to first-time author Reuben Roth about his book, Recruitment Debt: A Glossary of Terms to Help You Hire Your Next Great Candidate, what pushed him to want to write it, and how it feels to have worked with the right team to get it into readers’ hands.

Q: What made you decide to write a book to begin with, and what led you to reach out to Stuart for assistance?

A: Earlier in my career, I made a list of around 75 things that were core to the recruiting process. I reached out to people who I considered experts in the space to learn more about these things, which turned into a series of blog posts. In putting those together, I generated so many words I thought it might be beneficial to turn the content into a book. To do that I tried working with two different ghostwriters, but things stalled out. Maybe it was me, maybe it was them; it doesn’t really matter. The point is, the process pre-Stuart was too confusing and generally pretty rough. I had been dabbling for almost two years with no success whatsoever.

It was only after Stuart and I partnered up that the process finally started to work. He had me outline everything I thought I knew. Then, we filled in all the blanks. We grouped that content into different chapters–and in doing so settled on the glossary format of the book–and then Stuart re-interviewed me on all those chapters to flesh them out even more.

Q: What were the challenges of translating your complex, real life work into text in a book, and what were the benefits? How did squaring up to that effort contribute to the creation of the glossary, in particular?

A: Writing a book definitely pushed me to simplify the concepts I’m so used to talking about. That was a challenge, along with finding the theme that unites the different parts of what I do, and getting the tone right. The benefit was that I learned a lot. There were things I thought I knew well, but it turns out I didn’t know as much as I needed to so I had to dive back into the material myself. The glossary concept we landed on was key as it’s quite representative of the recruiting process; it makes it easy to take only what you need to build out the system that’s right for you. Not all companies need the full menu, they might just need a few of the pieces. I’m proud that my book reflects that, and is applicable to all use cases.

Q: What did the addition of the illustrations (a nod to your natural diagram prowess, SH says) bring to the finished product?

A: The illustrations keep the book lighthearted and help it flow. Sometimes recruiting can just feel like a list of things you have to do; things you know you should do, but things that take time and require extra work. So the illustrations being fun is important. And working with Molly was great. She was very autonomous which I appreciated, and even with that she managed to capture exactly what I wanted.

Q: What is the value in having completed this process and getting your book out into the world?

A: I have only positive things to say here. I appreciate that it gives me something concrete to point at when people reach out to me, but also, it’s just really nice when people randomly reach out and say they’ve read it. That’s part of why I’m in the recruiting space: having the opportunity to help people and give advice that means something.