It started innocently enough. In the margins of the novel I am writing, one of my beta readers wrote: “I like this repeating thing where X. accepts that people’s opposing realities can both be valid, and how it seems like an enlightened/healthy concept, but X. actually applies it in a sort of dismissive, undercutting way instead (even if he doesn’t realize it).”

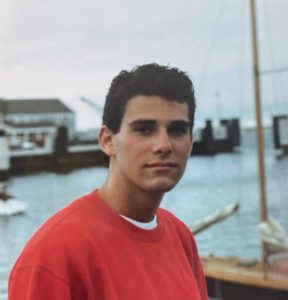

Um, what now? I’m glad my perceptive reader added that “even if he doesn’t realize it” part. Speaking for the narrator of my novel, if I may, I will say that no he didn’t realize that. He didn’t realize that his seminal trauma had effectively split his brain to where he could never really be sure if he belonged. And that when overwhelmed by the defensiveness that naturally proceeded from such a state, he envies the people who have been through worse than him yet who can still manage to act natural. If it comes off like he is judging them, it’s because it’s all he has left.

I don’t need to visit my therapist to realize this is all true of me as well. Besides, those appointments aren’t until Thursday. What I find most interesting about this projective exercise called creative writing, when brought before the eyes of a talented editor, is that — knowing this about myself now — I am faced with an understanding: If I want my character to grow along an arc, I will need to face that same arc along with him.

You might call it wish-fulfillment, but it is more substantive than that, these possibilities I can glimpse for both myself and for my narrator. The way each can heal the other. Risks will need to be taken, in fiction and in life. Stubbornness will have to be relinquished.

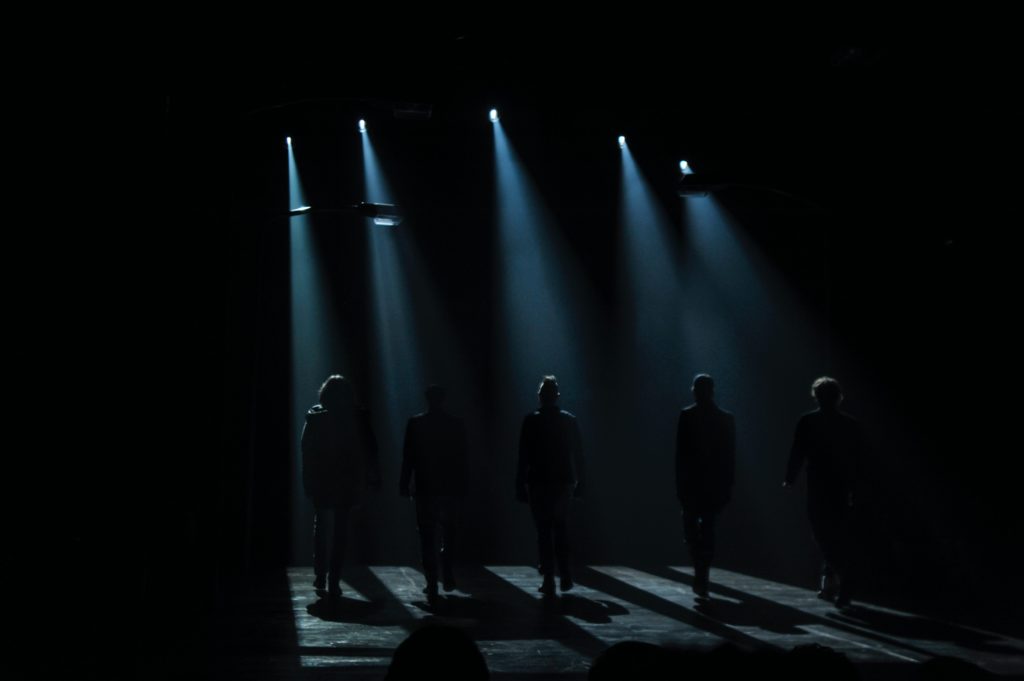

At the end, I’ll worry of course, if this novel will get published. Or made into a series for Hulu. Or both. But for now I am content to watch the way art and living refract each other, pointing down an as yet untraveled hall of mirrors, to greater self-understanding and enhanced self-efficacy.

At one point my narrator asks, “Who was I supposed to be in this context? Will it ever get to the point where there is one me in every context?”

You and me, my friend, we have the same goal. Let’s stick together and see where this thing goes.