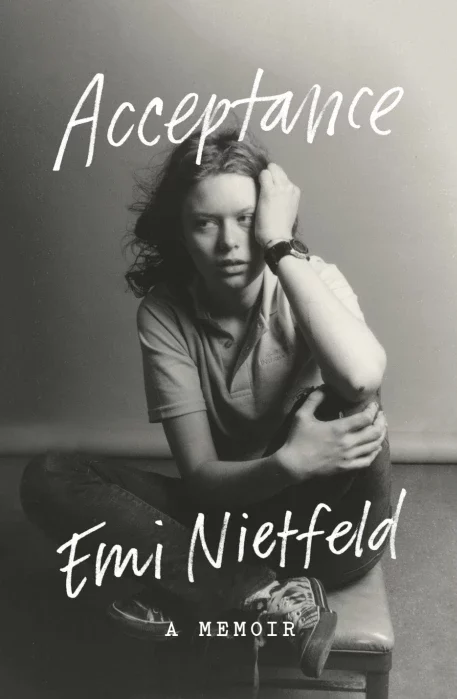

Madison Utley speaks to debut author Emi Nietfeld following the publication of her memoir, Acceptance, which tells the story of how a child faced with a seemingly endless series of challenges–including parental mental illness, foster care, and homelessness–and operating largely without the assistance of advocates, managed to propel herself into Harvard and beyond.

Here, Emi invites us into her writing process, explaining how she went about striking the right balance between factual integrity and structural clarity and sharing how Stuart’s book on writing, Blueprint Your Bestseller, helped her shape her manuscript into what The New York Times called “a remarkable memoir.”

MU: In the epilogue of your book, you tell readers about your experience of researching your own life. Your time as a child in the mental health and foster care systems meant you had thousands of pages of documentation to draw on. That information included many things you had forgotten, remembered differently, or couldn’t have known at the time. Talk to me about the process of reconciling that disparity.

EN: I started writing my book about seven years ago. I began by completely relying on my own memory. The serious research part didn’t really start for two and a half years, when beta readers of my earliest drafts continued to question my motivations in certain situations and I couldn’t actually remember the why.

Doing the research and confronting the facts from my past was one of the most difficult parts of the process. Every time I read the medical records or the emails or other things I came across, I was emotionally devastated. I often felt like I could not own up to what I actually did or said. I was mean. I stole things. I lied to people. But ultimately, I felt it was really important to be completely honest about my own mistakes and things I had done in Acceptance.

After spending time with the research, I went back and rewrote what I had already written to take into account the fuller picture of the truth. It became both about taking responsibility for my actions while not bogging the story down with every available fact.

MU: How did you balance your commitment to telling a more honest version of your story with presenting a well-structured, navigable narrative to readers?

EN: The detail available in my research introduces a lot of extra ups and downs in the story. Basically, I had to emotionally consolidate what I was thinking about in order to write it in a way that guides the reader without having them go over a bunch of those speed bumps.

There’s also always this struggle between telling an authentic story and the demands of the marketplace. That was something I grappled with a lot early on. But over the last seven years, both writing the book and writing some essays and shorter pieces, I became more comfortable with the idea that there’s not just one version of the story. Tying what happened in my own life to questions that are relevant in the world is actually a powerful way to connect with readers. I feel lucky that I had a publisher and a team that was really thoughtful about making sure that I was only saying things that really felt true to me.

For example, in my early drafts of the memoir, I was trying to present myself as an overcomer with this really inspiring story. In that version, I deserved to get into Harvard, to work at Google, to have these really great things in a world where so many people do not. But being more honest about my experience pushed me to find the thing that’s bigger than myself and my own story, which is this question of resilience and how the ideal of resilience can be used against vulnerable people. Over time, conveying that message became more important to me than having readers like me or read me in a certain way.

MU: Tell me more about how you honed in on that driving theme to center your story around.

EN: One of the best books that I read about writing is called 101 Things I Learned in Architecture School by Matthew Frederick. The main takeaway is that in architecture, to build a significant building, there is usually what’s called a parti behind it, a unifying principle. Every choice about the building emerges from that one principle. That idea was really useful as I considered how to make my memoir be about something and how to shape my story to have artistic unity.

Like a lot of memoirists, I had written early versions where the feedback was, “This is less of a memoir that has a focus, and more of an autobiography.” I was stuck there for six drafts, really, struggling to make it cohere. Then, a friend’s mom who’s a writer recommended Blueprint Your Bestseller and I really appreciated how it was so straightforward in laying out: here’s how to do this edit. I was able to go through that process in one month and do a complete revision. I went from 400 pages to 200-something. The feedback I received from beta readers looked dramatically different. Before, I had to beg people to read it and after I did that revision, people would read it in one or two days and there was a lot more excitement.

MU: What has been the most unexpected part of getting your memoir into the world?

EN: The thing that’s been surprising to me is how many doors having published this book have opened up and, I think, will continue to open. Maybe that seems obvious, but I was so focused on getting this out as the goal. But now, to have it published and for it to have gotten good reviews, as well as having been able to publish essays along the way, I feel like I’m in a totally different place in my career than I was before it came out. I have this feeling of, “Oh, there are more directions that I can go.”

I’m not from the literary establishment. I studied computer science. I was working in tech. Moving towards getting this book published felt almost like being a pawn in a chess game, where in any situation there were only two moves that I could make and I had to keep making those moves over and over again. Now, I’m a rook and it’s great. I have more moves I can make. It feels like there’s a lot of possibility.

Committing to my business full-time and being in control of my own destiny has had a huge impact on how quickly I’m able to clear my mind before a good writing session starts. Now, there’s a lot of cross-flow between the work I do for Book Architecture and the work I do for myself. I can do my job for five hours and then I can take a break, exercise, meditate, go to the coffee shop, whatever, and then write at night. I’ve created the context and learned the tools I need to access that headspace.

Committing to my business full-time and being in control of my own destiny has had a huge impact on how quickly I’m able to clear my mind before a good writing session starts. Now, there’s a lot of cross-flow between the work I do for Book Architecture and the work I do for myself. I can do my job for five hours and then I can take a break, exercise, meditate, go to the coffee shop, whatever, and then write at night. I’ve created the context and learned the tools I need to access that headspace.  We’re excited to share that friend of Book Architecture and industry stalwart, Lisa Tener, has launched her new book, The Joy of Writing Journal: Spark Your Creativity in 8 Minutes a Day.

We’re excited to share that friend of Book Architecture and industry stalwart, Lisa Tener, has launched her new book, The Joy of Writing Journal: Spark Your Creativity in 8 Minutes a Day.