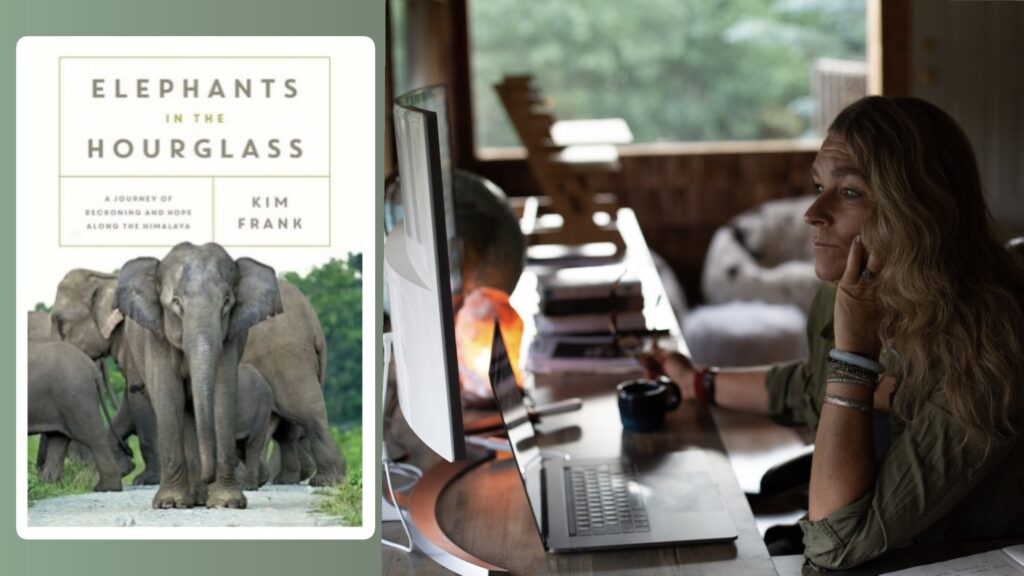

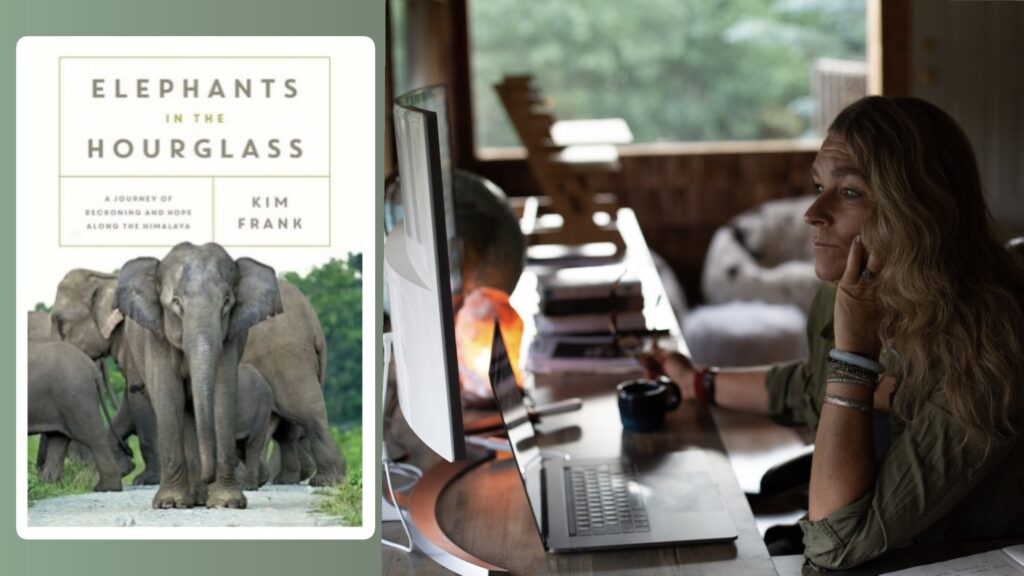

Stuart Horwitz speaks to writer, photographer, and documentary maker, Kim Frank about the years-long process of writing Elephants in the Hourglass: A Journey of Reckoning and Hope Along the Himalaya, published by Pegasus Books earlier this year. Frank shares what kept her motivated throughout, her commitment to authenticity during the sometimes challenging promotion phase of authorship, and why she so ardently believes in the importance of refusing to rush through revision–or any part of the creative process.

S: How long did you work on this book? From the moment you got the idea to the time you held a copy in your hand.

K: I went to India for the first time in the spring of 2018, and soon realized I couldn’t possibly tell the whole story from just one trip. It’s so complicated, so culturally imbued. I wasn’t sure what the project was going to be then. I thought it might be a magazine article, or maybe a documentary, perhaps a book. That’s when Anthony Geffen, the founder and CEO of Atlantic Productions, took a look at my stuff. I had photographs and field notes spread out on his kitchen table. He told me, “You need to write the book in order to figure out what the story is–then you can consider a documentary.”

I was a fiction writer so I didn’t really know how to tackle a full-length nonfiction book. At first, I was in despair. As you know, because that’s when you and I talked. The first time I ever had a call with you, I was about ready to give up. And you stopped me from giving up, so thank you for that. Around the same time Anthony, who had become a mentor to me, said something that I’ve carried with me since: “Kim! Sometimes you have to fight for the story!” And so that’s what I did. I thought about the people I met in India. The people who gave me their trust there, their time, their story, in the hopes that I would amplify their voices and make them feel seen in a way they haven’t before now. And then there’s the people who invested on the home front–my husband, my children, my parents–all those who gave me the time and space to write. It was all of them who helped me not give up over the years of working on this project. I felt this incredible responsibility to finish because I wasn’t just by myself anymore. Six years later, in January 2025, I held a copy of the book in my hands for the first time.

S: Let’s talk about promotion. How do you make it authentic, and how do you keep yourself fresh when you’re answering the same questions over and over?

K: The more time I’ve spent working on this project in India and beyond, I’ve come to really believe there’s a force bigger than me at play. I’m a vessel. I’m just doing my part: the storytelling, the authenticity. As long as I stay connected to the elephants’ energy, to the thing that’s bigger than me, all will be smooth. The way will open, whatever that’s meant to be. The challenge is the more you have to promote your work and promote yourself, there’s this real danger of the ego becoming bigger. “Oh, I didn’t get invited to speak at that event. What’s that about?” “Oh, that person’s book is getting more attention than mine.” This growing ego feeling is very different from the connected channel I had been able to tap into when I’m focused on the creative piece of it.

But I do love talking to people who get it. I really love doing interviews. I especially love when people have an open mind and heart that can talk about the more ethereal bits involved in the creative process. I really have enjoyed talking to people like you that I care about, that have helped me along the way. Second to that, I like doing talks because I feel like I’m able to connect with people and I’m able to bring the story to life through myself. There are parts of promotion that I am actually having fun doing.

S: I feel as if your commitment and perseverance is a talent. Without that personality trait, as a writer, you’re cooked, really. You’ve got to be somebody who can say, “This is what I’m doing; I don’t know whether it’s going to be a success or not. I don’t know how many years it’s going to take. I don’t know whether you agree with me or not…but this is what I’m doing.”

K: I’d love to speak to that from a craft perspective. I often hear writers say, “I’m a one-and-done. I wrote that draft to the end and it’s good enough.” For me, and what I want to teach others, the art is in the revision. Revision is where you meet the creative gods. You have to get the whole thing on paper first, and then the work begins. Then, the art begins. It’s like a sculpture. You have this great big mass and you have a vision for what you want that hunk to look like and through revision, revision, revision, all the shaping, all the detail comes out. So if you’re not in love with the process, you won’t finish the work the way it needs to be finished. If you’re in a hurry to get to the end, the end is going to feel really hollow.

People say to me, “You must be so excited to have your book in your hands!” And yeah, I’m thrilled to be holding a physical book from a traditional publisher, that I had an agent for, all those things. But if I rushed through writing the book in the hurry to get an agent or to get it published, I would have missed out on the growth of myself as a creative human. People on the outside would ask me, “Isn’t it good enough now? Why do you have to keep writing it?” Because it wasn’t done. It’s a process. It has to nourish you. It can be frustrating as hell sometimes, but the process also has to nourish you or else what are we doing?

S: It is frustrating and there are so many unknowns, the biggest being: is it going to reach this hard to define level of success we carry somewhere in our minds?

K: And you can’t control that. You just have to get out of your own way. If we grip too hard to something we want, sometimes we block the path for what’s possible. Right now with promotion, I know I need to be doing all these things. I need to be promoting the hell out of the book. People have to be doing the Amazon reviews and all the things, but there’s also part of me that thinks it will seek its own level somehow. I want to be more focused on: Who am I every day? I can’t become preoccupied with how successful the book is or isn’t… In my opinion, if the book has made a difference in someone’s life or if it inspired them in some meaningful way, that’s a win to me.

It’s very easy to get out of balance. I’ve done a lot of work to deepen my practice: my yoga practice, my mantras, my spiritual connection, and build the tools necessary to take it on the road, so to speak. When I’m at home, it’s easy to have that balance. But when I’m out traveling things begin to feel overwhelming. So I’m recognizing that exercise–for me, yoga and what yoga means as far as its spiritual practice–is as important as hygiene, and I need to constantly prioritize it as such. You never question, no matter where you are, if you’re still going to bathe and brush your teeth. I haven’t yet mastered incorporating those elements into my daily hygiene to where I prioritize it on the road as well as I can prioritize it when I’m at home, but that’s the goal.