We’ve left it open for you, so you don’t even need one of those little keys. Because writing is life, and keeping it real means forgoing the line between the personal and the professional.

The Act You’ve Known for All These Years

This article was originally posted on the Good Men Project website.

What do you do if are a father of a daughter who loves to perform? If you’re Stuart Horwitz, you go busking with her.

We wake up day after day to the sound of our daughter singing somewhere in the house. On different mornings, we take her singing to mean different things. We tease Fifer about how perfect everything is, and she’ll say, “I admit it. I love my life!” Underneath this repartee is a sadness that Bonnie and I try to keep from becoming real jealousy. We envy her unconscious joy in living, the ability a ten-year-old has to just brush off the hurt and wake up singing. Other days, her singing reminds us that she is a unique individual, a product of her parents, but with something else mysterious thrown in.

It used to drive me insane that my daughter didn’t like to read. She could; she would. She just preferred to cut designer fashions out of paper and adorn them with tiny beads and messy glue. Me, my whole life is words. I coach writers, I teach writing, I write. Then something happened in my mid-thirties, when my daughter was six or seven: I stopped reading. I brought crates of novels to a used-book store and traded them for a T-shirt. I started to look at the world more directly, without the filter of black lines across white pages. I picked up the guitar. How sweet it was to make music, to bang on strings and sing to myself—this simple lesson I learned from my daughter on those mornings when I had ears to hear. No one was recording me; I wasn’t going to make a name for myself. Something even better was emerging: I was alive.

****

One day, when Fifer was eight, we received a notice that our local community center was hosting tryouts for The Wizard of Oz. For the auditions, kids had to sing a song without any accompaniment. My daughter learned “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” with help from her grandmother and Bonnie, and then they trundled off to the audition.

“They wouldn’t even let me be a Munchkin,” Fifer said upon her return, with a disappointment that was not tinged with bitterness, if an adult can imagine such a thing. And this is a kid with perfect pitch. I’m not bragging, because her talent doesn’t come from me. We had started learning some songs together, with me on the guitar and her on vocals; I would look over at the tuner, during an obscure part of the Beatles’ “Within You Without You,” for instance, and she would be right there on the B-flat. I remember a friend of hers, a kid symbolically named Dylan, once asking her, “Why are you always singing?” Fifer replied, “Because it’s my destiny.”

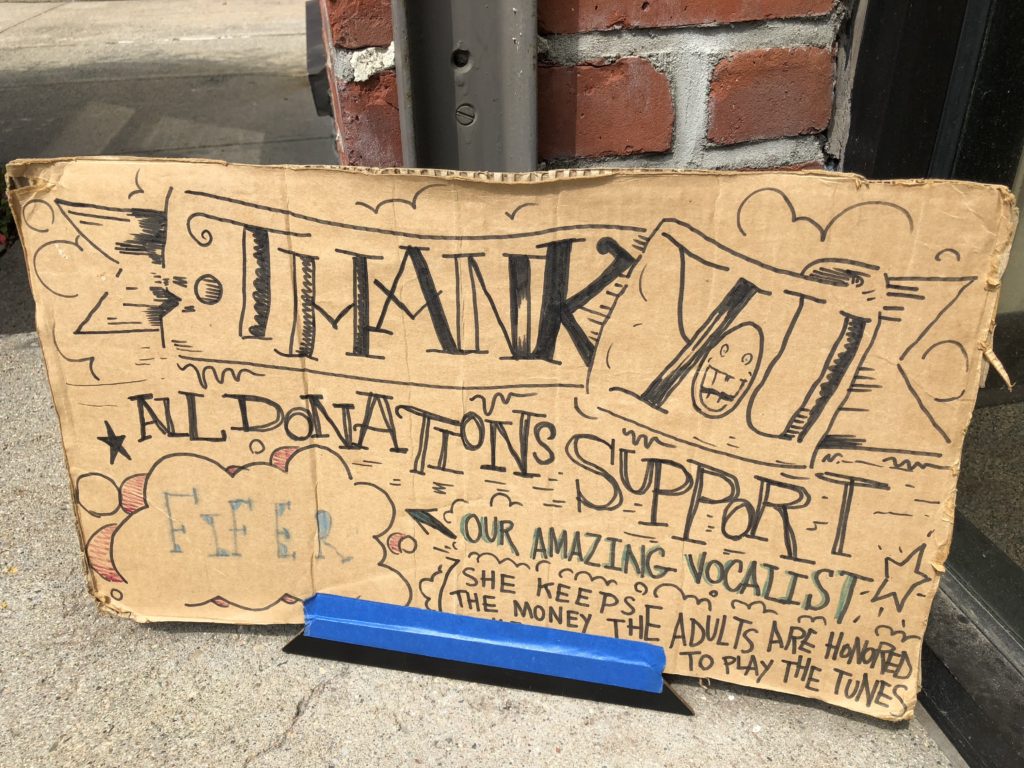

Besides being fated to become a vocalist, my daughter loves money (she’s a Capricorn). To see this trait so apparent in a child’s eyes was a little shocking, but it gave me an idea: We would step it up on the songs we had been practicing—which made me happy, fulfilling my role as the father who was supposed to make her stick with things—and then we would play them on the streets for money. Busking is what it’s called; we learned that term together. “Some dads take their kids fishing,” Bonnie said. We would perform Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band straight through twice (with the exception of tracks two and four, which we never got around to learning). Though Fifer vowed me to secrecy—she wanted to keep her “normal girl” status, playing softball (pretty well) and viola (no worse than anyone else in third grade)—she looked forward to our “gigs” as much as I did.

Her enthusiasm for performing didn’t surprise me. One time when she was about three, we attended a crowded story time at the local library. After the reader had stepped down, Fife crawled between all the sprawled-out kids and patient parents and got into the big chair. Then she picked up a book. “Now it’s my turn,” she said. She couldn’t read yet, so she sort of performed the book by looking at the pictures. The reader, an older gentleman who was vaguely famous, came over and clapped me on the shoulder. “I’ve never seen that before. Good luck, Jack.”

Maybe it was genetic. In my early twenties, as a performance poet, I had stood in front of the American Express office in Prague after dawn, declaiming Bob Dylan lyrics, with a hat placed on the sidewalk to collect tips.

****

Busking is a genuine artistic experience. No gatekeepers determine whether you’re good enough; the audience does. People either dropped money into our guitar case or they didn’t. Some, like the crowd outside Fenway Park, were surly and drunk and not into having their hearts moved by a young girl. Others were encouraging, like the woman who told Fifer, “Jesus loves you, honey.” Fife turned to me, and without a trace of irony, said, “That’s so nice!”

We had hecklers. My ex–business partner said, “You’re teaching your kid to beg, huh?” But in what other job can an eight-year-old make over $300 in one summer? Fifer gave some of the money she made to charity, and she put some in the bank for a car, but then she bought herself a powder blue iPod Nano, for which I paid only the tax. It was a proud moment in my parenting career.

We didn’t do it for the money, of course. There were times when we would be walking to our spot, and one of us would freak out a little and ask, “Why are we doing this again?” And the other one would respond with what became our mantra: “To face our fears!” We did it for that moment after we had set up our music stands, when we had taken a deep breath and were looking around for a sign that we knew wasn’t going to come from anywhere but inside us. And then we would start.

I can hear Fife now, imitating Paul: “One! Two! Three! Fo! [We’re Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band / We hope you have enjoyed the show…]” It was always easier when a few people she knew were in the audience; then if, for instance, the high-E string on my electric guitar broke during “Lovely Rita,” we could get other people to sing and clap along. Other times Fife couldn’t get started at all. That’s when I would forget about the weight of the amps that I had to carry and forget about my own need to be heard, which was always lurking. I would be ready to pack it all up again if I had to, and I’d offer to do so. Then maybe the cloud would pass, and I could coax Fife back into connecting with her confidence.

“It always feels better to play than not to play,” was one of the quotes Fifer wrote down from those days—she chronicled every show we did over the span of two summers. Besides the good lines, she recorded the set list, the screw-ups, the amount of money we made (of course), and the magical moments. She wrote about the time on Boston Common when we drew a crowd only after a dying pigeon named Sam did his diseased circle dance in our guitar case. Then there was the time we had just finished a set of Sergeant Pepper’s and an eleven-year-old girl came up to Fifer and asked, “Did you write those songs?”

Some things she didn’t write down. My father and mother came to see us and listened as we performed “She’s Leaving Home.” I sang John’s chorus: “We struggled hard all our lives to get by…What did we do that was wrong?” I’m not sure how much of the healing my father and I were doing was conscious, but afterward he bought me a state-of-the-art portable recorder to capture our best tunes. “What does that mean,” Fifer asked, “She’s leaving home after living alone for so many years?” You will never know, I said.

The shows went on, and we had our ups and downs. There were great moments. A female drummer—Rachel—joined us, and she did the best-ever “Ah-ah-ah-aahs,” in “A Day in the Life.” A rhythm section—Robbie and Timmy—filled in for Rachel one night and then never left. My daughter, now nine years old, was fronting a Beatles cover band. Yeah, that made me proud.

Then there were nights when she wanted to go to church or a school party. But we had already made all of our arrangements, and you can’t just cancel on other people at the last minute…

New York was probably our finest hour, blasting through a punk version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in defiance to what had started the whole experience, or holding an a cappella sing-along during Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” (we had increased our repertoire by then). A guy named Adam approached us in Washington Square Park, offered us fruit, and called us “his lovelies.” “You have helped me feel free again,” he pronounced. Somebody else said they wanted to make a documentary about us.

And then Fifer said she was done. She gave no reason, until I pushed, and then her reasons kept changing. “There’re too many kids here,” she said one night in Newport, when we drove away from the town without ever playing a note. (Was she getting self-conscious now that she was approaching preadolescence?) Or she would say, “I’m bored.” But how can you say that? You had your arms up in exultation after your last performance, squealing, “That was so fun!”

Then I recovered a little Zen. It is what it is. Stop asking questions. Don’t accuse her of being lazy, not committed. Let it go and be there for her in the way she needs you to be. Keep learning the lessons at hand.

****

Three months after our last gig, someone e-mailed us about an upcoming audition. The national tour of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was coming to a stage much bigger than the one where The Wizard of Oz had played. Did she want to go try out? Because it was totally up to her; I wasn’t going to take the rap as some pushy stage father. Yes, she said. And yes again, when I asked again later.

The ornate lobby was crammed with kids warming up for their well-taught dance routines. Eighty-six kids were trying out for seven spots. When a ten-year-old next to me belted out “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” I thought it was Ethel Merman herself. “Well, it’s a good experience,” I told Fife. “Think about all the people who aren’t even here. There’s no way they’re going to make it—right?—if they’re not even here?”

Fifer was going to perform her last, best busking song, the one we would play over and over again in Central Park, when the tourists couldn’t give two shits about us: “…And you, take me the way I am.” They took the kids away in groups of ten, leaving us parents in the lobby.

“Tell me again how she said it?” I asked. Fife had returned to the lobby, and I wanted her to describe precisely how the judge had responded to her performance. Fife went through a few different intonations until she was satisfied with her delivery: “Wowwww!”

I was the first in the house to find out Fife had been picked for the part. I bought the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang DVD and played the theme song loud enough one November morning to wake everyone with the news.

That night, I wanted to watch the movie. “Dad,” Fifer said, “the performances aren’t until March.”

Apparently I was still learning, about nonattachment, about doing the thing that is to be done in that moment, about being there for somebody even when what they need is changing too fast for conscious record. Then I settled into our rematch of Sorry! Sliders, trying my best to beat her, because that’s how we do things around here.

I love this! As the mother of a singer and dancer, as a singer and writer myself, wondering how my daughter could not love to read anymore… All the letting go, all the joy. Way to go, Stuart

Thank you, Kathe! And yes, my teenager refuses to read. She does however ask me for “Word of the Day,” so I guess that’s something. Recent choices: ubiquitous, splendiferous and everyone’s pandemic favorite: unprecedented.

This is such a heart-warming, lovely story. It reminds me of the interesting and special moments I have with my grandchildren, chats, watching their sport, reading with them, and tales of school.

Thank you for reading! And for your contribution to your own young one’s lives.

I loved this. You are such a good father. I could tell that by other things you’ve written, such as your piece about your “Amnesty Day.” I sent that to my adult daughter who is a mother herself. She loved it as much as I did. Since you are a great Dad and a great writer, I think you should combine the two by writing a memoir, along the lines of My Life as a Father. I’ve read memoirs by women writing about raising their children, but not many by men. Go for it, Stuart. I know it would be well received by parents and those with no kids alike. Sounds like a winner to me.

Well, Linda, you are in luck! That is exactly what I have been working on for the past three-plus years. You will be the first to know when it comes out. Thank you again.

I love this so much I watched it three times. It’s events like this that have made Fifer the confident young woman that she is.

What a nice thing to say, Mel! It has a lot to do with the other members of Fifer’s family, starting with your sister, her mother!