Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the novelist E.L. Doctorow’s quote in the Paris Review Writers at Work (2nd) series. You may have heard it:

“Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

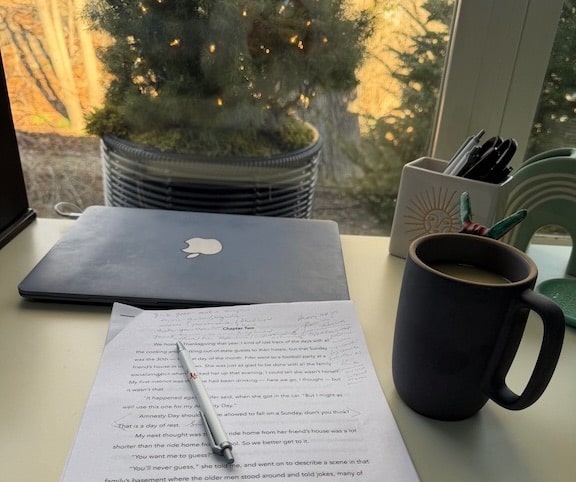

I believe this; I really do. But still I struggle, writing a book on a deadline, when I extrapolate my current word count and it inevitably falls short of what my contract stipulates. I experience anxiety over not being able to see the make-up of each and every chapter clearly from where I sit today. And behind all of that is the concern that, while I like what I have done so far, that is no guarantee that I will continue producing at a high level.

Rather than make myself falsely feel better, which will only be a temporary solution, I find myself going back to the quote and asking it questions.

If that is true, then I should implicitly only worry about what my headlights illuminate, right? So, it is okay to write Chapter 8, and then Chapter 4, Chapter 3, the Introduction, and so forth?

And if I do that, can I truly rely on the Book Architecture Method concept of series to help me keep track of what I have written about, what still needs to be seeded, and what needs to be concluded?

And if I stay committed to this approach, is it okay, natural even, when one chapter splits into two, and the 33 ideas I have here go with one grouping, and these 15 ideas go with another? And then I can complete this chapter that uses those 33 ideas as their base, and assume that the one with 15 ideas will grow under the approaching headlights the same way all of the other chapters have grown?

Then my obsession with surety always comes back; it seems the best I can do is alternate belief and doubt. I re-read the quote and ask: What if we’re on the wrong road, though? I spread the paper map out on my knee while I am driving, which if you didn’t come of age during the era of paper maps, is not only dangerous, but you end up missing the clues of where the road winds and dips ahead. Are you sure these high beams are on?

There seem to be two options: self-torture or faith.

If I choose self-torture, the activities seem pretty clear. I will measure and stress over quantity and pace. I will grasp for ideas whose time has not yet come. I will try to get some unsuspecting beta reader to make me feel better about my progress and eventual destination, etc.

If I choose faith, there doesn’t seem to be much more to it than this: Sink into the work. Do I know what I’m working on Tuesday? Do I have a process to capture what announces itself then over the horizon so I know what I’m working on Wednesday? If so, I have everything I need.

Maybe this is why the novelist Ernest Hemingway praised incremental progress:

“The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day when you are writing a novel you will never be stuck. That is the most valuable thing I can tell you so try to remember it.”

Meaning, if you can see this swath of highway, you’re good. And what’s more, once you get a glimpse of the next stretch, you should save it for tomorrow as a way of avoiding writer’s block.

Some days, it all makes sense. One those days I might remember another quote, this one from Japanese Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki:

“Your way is to kill two birds with one stone. Our way is just to kill one bird with one stone.”