We’ve left it open for you, so you don’t even need one of those little keys. Because writing is life, and keeping it real means forgoing the line between the personal and the professional.

Clients Crushin’ It: Beth Monaghan & InkHouse

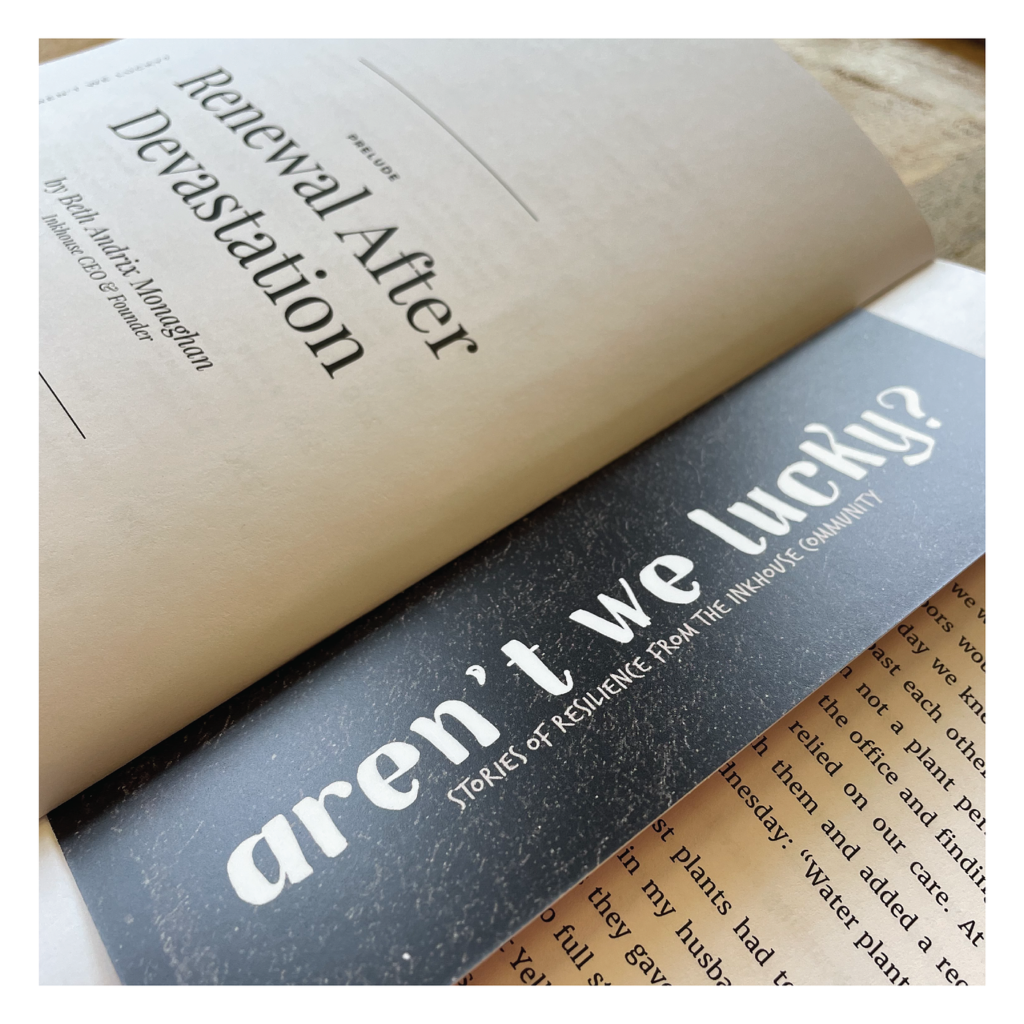

Madison Utley speaks to InkHouse PR founder & CEO Beth Monaghan following the release of Aren’t We Lucky? — the company’s second collection of employee-authored stories, and fourth content project supported by Book Architecture.

Q: How did you arrive at the idea of creating a company book, and why did it seem like the most fitting way to deepen the culture you’ve been cultivating at InkHouse?

A: The books evolved out of the Inkies, a Moth or TED Talk style event we used to do with Book Architecture. We wanted to design a creative outlet for our people to hone their skills in storytelling, writing, and presenting — things we do for a living. But at the first Inkies at the Old South Church in Boston, something magical happened: we all felt so much more deeply connected, including the people who didn’t present.

My sole regret was that we only got to hear five or so people’s stories. A live event naturally constrains the number of participants. Plus, there’s that heart-stopping fear of spilling your guts in front of coworkers with no notes to guide you. So the first book of essays was hatched. I was expecting ten to fifteen essay submissions, but we got 44!

Q: What about the experience of creating the first collection of essays, Hindsight 2020, encouraged you to produce Aren’t We Lucky?

I watched Hindsight 2020 change our people, and it also changed me. Who doesn’t want to do that again? In the fall of 2019, I set aside three days to read all of the Hindsight 2020 submissions. Candidly, I was expecting to have to haul myself through them, but as I read, I was swept up.

Those essays shed my previously unconscious belief that the best stories are at the library or at the bookstore. They’re not. You just need to ask the person sitting next to you, but we rarely do. And I thought — this is how we get to understand each other and draw nearer. This is how community forms. It also helped that so many InkHouse people told me it was their favorite event of the year.

Q: On the employee side, writing a personal essay knowing it will be disseminated to your coworkers and beyond requires emotional vulnerability and, frankly, a specific kind of hard work. Yet it seems that the InkHouse team has been thrilled to embrace the challenge many times over. Why do you think that is?

I believe that each of us have a few stories we’ve been burning to tell. The telling gives us a chance to be seen in an environment that’s rooting for you. But it’s freaking terrifying. I can feel the presenters’ nerves each time. Hell, I’m nervous! Then I see them become their whole selves as they read their work. And then their co-workers are crying or laughing and clapping. The look of pride on their faces is something I will always carry with me.

Q: From the leadership side, it seems that significant company resources must go into large-scale culture building initiatives such as these books. Why is that worth it?

A: When people ask me what I like most about my job, I always say it’s these projects. I feel slightly embarrassed every time—I should say PR because that’s what pays the bills. But these efforts are part of how we build understanding and community. Without both of those things, the PR work doesn’t get done well.

We have more than 130 people who work here and it’s so hard for me to get to know each one individually. Projects such as these allow me to get to know so many of our people in a way no work assignment can. It helps me understand them as human beings, which helps me better know what our workplace needs.

Q: Beyond the baseline benefit of making employees’ day to day lives tolerable, why does investing in a workplace culture that allows people to be their best and truest selves matter? And what is the value of capturing that in book form?

A: I’ve spent many years fighting for social justice around gender and race. The problems are so big that it can feel like nothing we do is enough to solve them. And it’s not. However, if we do the thing that’s right in front of us, and then the next thing, and then the next, we can collectively begin to make change.

As I see it, part of my responsibility to that change is creating a workplace that values differences in the creative process at work. This requires us to welcome employees as they are. We can’t do that if we don’t understand each other. We have to actually talk. Our books are the most important way we do that at InkHouse.

Instinctively, we know that every draft is different. In the first draft, we can’t really be held responsible for the exact quality of what we produce; we just got here, ourselves. We are just trying to cover the ground. In the second draft, we might be learning the ropes a bit more. We can say what the better stuff is that we are trying to bring up another level. By the third draft, we are ready to polish, decide, and hopefully finish something.

Instinctively, we know that every draft is different. In the first draft, we can’t really be held responsible for the exact quality of what we produce; we just got here, ourselves. We are just trying to cover the ground. In the second draft, we might be learning the ropes a bit more. We can say what the better stuff is that we are trying to bring up another level. By the third draft, we are ready to polish, decide, and hopefully finish something.