We’ve left it open for you, so you don’t even need one of those little keys. Because writing is life, and keeping it real means forgoing the line between the personal and the professional.

Clients Crushin’ It: Dominique Mielle

Madison Utley interviews Dominique Mielle – financial phenom, self-identified daredevil, proud Franco-American – ahead of the release of her first book Damsel in Distressed: My Life in the Golden Age of Hedge Funds.

***

Speaking to me now, in March 2021, just months before her memoir is set to be published by Simon & Schuster, debut author Dominique Mielle admits: “Was I confident we were going to pull this thing off? No. I certainly had my doubts.”

Long pause.

“But not in myself.”

This. This is Dominique Mielle: a woman with a straightforward commitment to hard work, to staying true to herself, to surrounding herself with excellence. It’s not a matter of conceit, it’s a matter of fact.

The confidence is certainly warranted when you consider who Dominique is; she joined a little-known hedge fund in the ‘90s, and stood decades later as the only female partner and senior portfolio manager running what had swelled to become one of the largest hedge funds in the U.S.

At the end of this impressive career in the “golden age of hedge funds,” Dominique retired; but, rather than coast (if it’s not yet clear, this isn’t a woman we should ever expect to coast), she circled back to her early aspirations of becoming a journalist. She thought of her recurring column for Forbes. She thought of her contributions spanning just about every publication in the financial sphere. She thought of writing a book; and so, that’s what she set out to do.

Dominique was sure that her voice – breezy but intense, bright but unapologetic – would add much-needed depth to the male-driven narrative dominating the hedge fund industry; she describes her tone as being loosely-inspired by Sex and The City and has been known to quote Samantha Jones on occasion (“I love you, but I love me more”).

“I knew I had developed a distinct voice,” Dominique explains. “I knew I could nail a 1,000-word piece, but I didn’t know how to carry that into a 60,000-word book. It was clear to me the first step was finding excellent help.”

True to form, Dominique would accept nothing but top-shelf guidance in making her book a reality. She found it in the second writer she reached out to. Enter: Stuart.

“Contacting just two writers is really not a lot. But with Stuart, we connected from the beginning. And that was it,” Dominique says.

“This is a relationship that matters. You’re spending a lot of time with and energy on this person. I even just remember thinking, ‘This is someone who will laugh at the same jokes as me.’ Building trust matters. This is a person you’re entrusting with your story.”

The wisp of a reservation Dominique harbored upon partnering with Stuart at the start of the project – what she describes as her “natural skepticism” sure to arise when allowing an unknown quantity into her process – was dashed in the earliest stages of working together. The moment of certainty came in receiving the first draft of the manuscript; then and there, Dominique remembers realizing, “Stuart is someone excellent.”

Rather than the external help tainting or suppressing the integrity of her story, each stage of the Book Architecture method was crafted to capture the best of what Dominique had to say, helping her voice carry true and strong throughout the manuscript – a dynamic clearly exhibited in one of my favorite excerpts from the upcoming book:

“Lehman filed for bankruptcy on September 15, 2008 and was eventually liquidated. Christine Lagarde, who was Finance Minister of France at the time (the first woman to hold such a position in a G-7 country), and went on to become the Chairman of the International Monetary Fund (the first woman head) said the following….

And I am not citing her because I admire her sense of fashion, although I do, or because she is French, although she is, or even because she was a synchronized swimmer as a child, and I have a weak spot for incongruous amusements.

I quote her because she might be right: ‘If it had been Lehman Sisters rather than Lehman Brothers, the world might well look different today.’”

While Dominique initially considered the writing process to likely be the primary takeaway from her book project, the refinement achieved through each draft made getting her manuscript published feel increasingly achievable. And, here we are.

Damsel in Distressed is the first hedge fund memoir written by a woman. In it, Dominique’s inimitable blend of intelligence and humor is used not only to provide insight about what it’s like being a female hedge fund manager in a business dominated by men, but to make clear she is “unwilling to be minimized by genderism.”

***

Pre-order Dominique’s book here, ahead of its August 24th release.

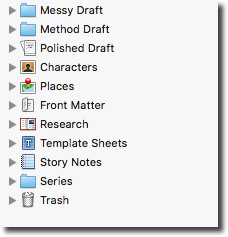

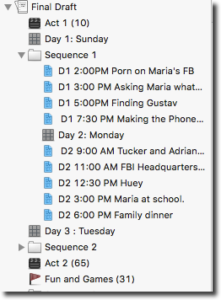

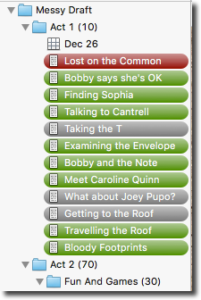

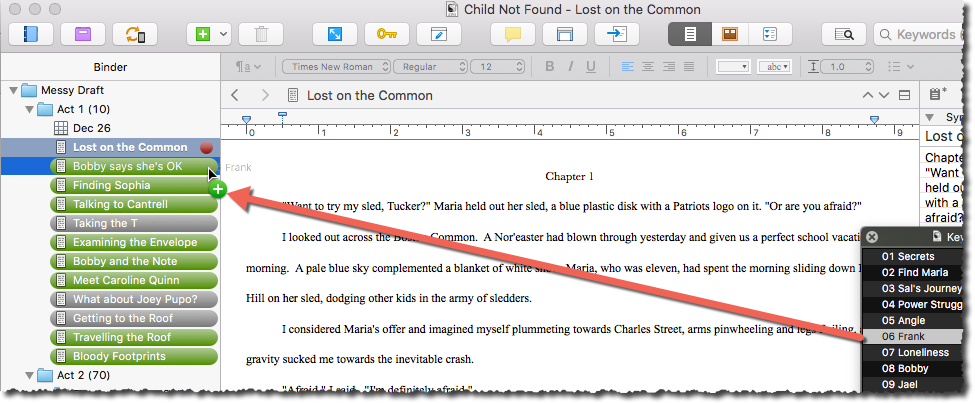

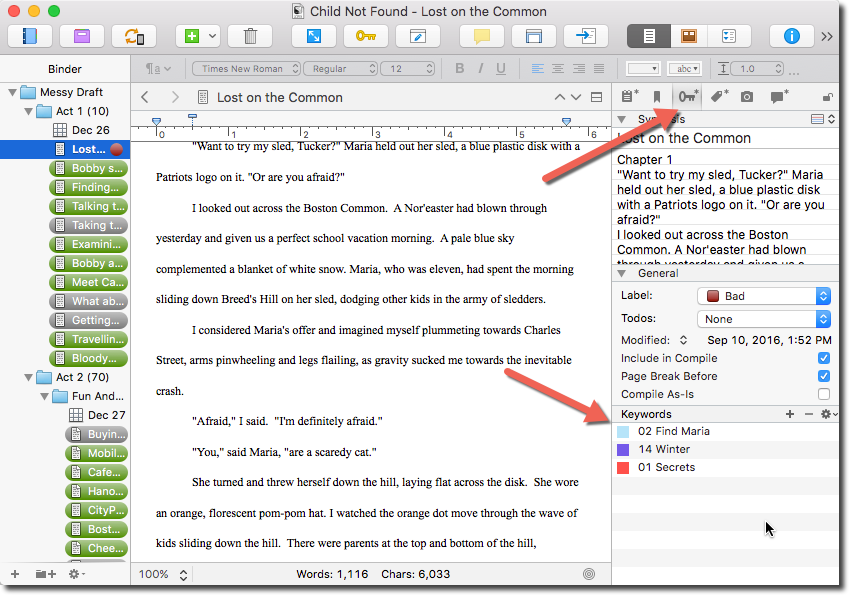

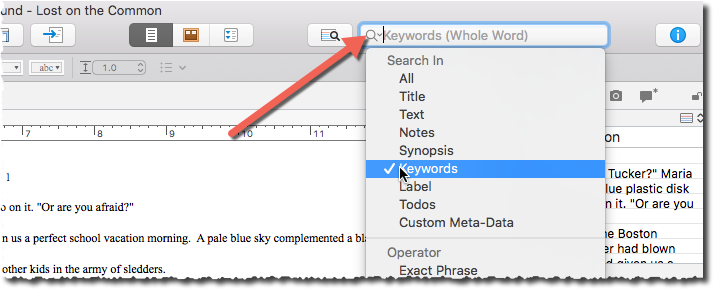

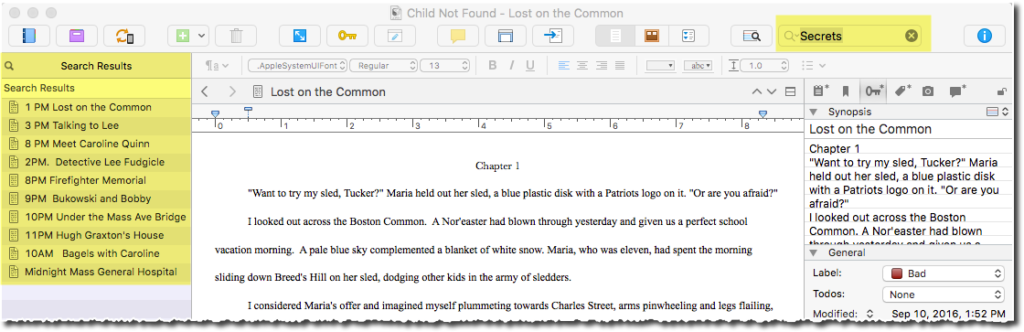

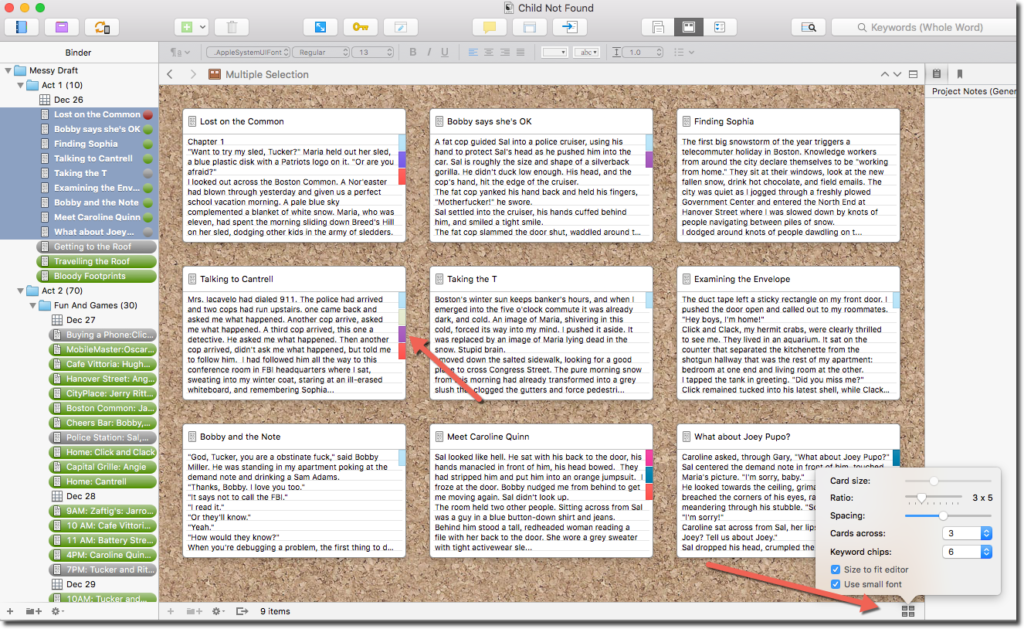

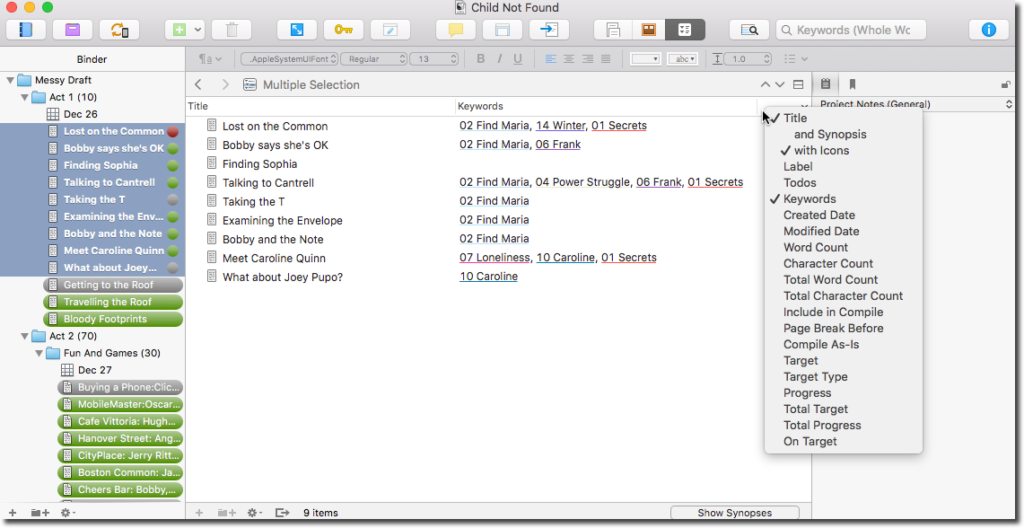

The first thing to notice is that my binder contains the three drafts Stuart outlines in

The first thing to notice is that my binder contains the three drafts Stuart outlines in

Fast forward several years and I’m currently based in Sydney, Australia (…because it’s beautiful. Because I want to. Because I can?). Some weeks, I’m elbow deep in projects that set my mind afire. Others, I’m trekking for days at a time through the Tasmanian wilderness. I’m dizzy with gratitude I’m able to structure my life in a way that allows me the freedom to pursue the breadth of that which I find fulfilling.

Fast forward several years and I’m currently based in Sydney, Australia (…because it’s beautiful. Because I want to. Because I can?). Some weeks, I’m elbow deep in projects that set my mind afire. Others, I’m trekking for days at a time through the Tasmanian wilderness. I’m dizzy with gratitude I’m able to structure my life in a way that allows me the freedom to pursue the breadth of that which I find fulfilling.