This article was originally posted on the Today Show website, following their publishing an excerpt from my upcoming memoir Amnesty Day.

By: Laura T. Coffey

A Rhode Island dad made what he described as a “calculated gamble” and won the prize of all parents’ dreams: an open, honest line of communication with his daughter throughout her teenage years.

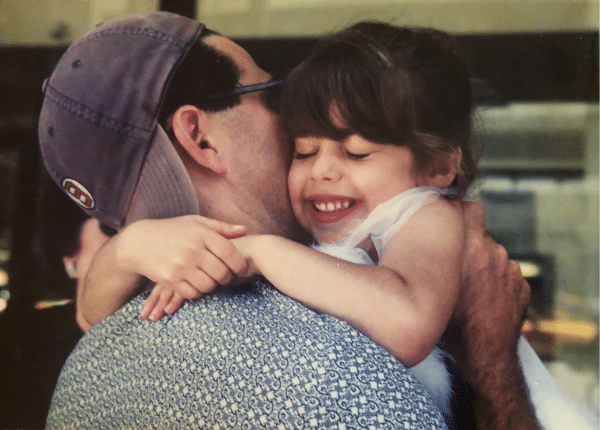

The gamble centered around a concept Stuart Horwitz dubbed “Amnesty Day” — a monthly opportunity for his daughter to come clean about absolutely anything without getting grounded, guilted or otherwise punished.

Horwitz said he felt the need to try something when he sensed that his daughter, Fifer, was starting to withdraw and withhold information in her 10th grade year.

“I could tell that she was holding some things back that she needed to let out,” Horwitz, 51, a writing coach and editor, told TODAY Parents. “This is an iffy time period for teenagers. They have to talk to somebody and most of the time they’re going to tell their friends, but teenagers don’t have enough experience to figure things out together.”

So, during one of their 40-minute commutes to Fifer’s high school, Horwitz suggested a “tell me anything” Amnesty Day on the last day of every month. He recalled feeling both relieved and terrified when Fifer said yes.

Fifer felt the exact same way.

“My dad was my buddy for my whole life and I always told him everything,” she told TODAY Parents. “But then I felt like there were things I couldn’t tell him anymore — and he could tell. I remember him saying, ‘Just tell me. It’ll be OK. You can just say it.’”

Horwitz chronicled the parental roller coaster ride — and the ultimate successes — of his daughter’s monthly confessionals in a personal essay that he shared with the TODAY Parenting Team community.

“On Amnesty Day, I heard about the night she wandered around Providence on the drug ecstasy wearing only her socks for footwear,” Horwitz wrote. “I learned who bought her fake I.D.”

Horwitz acknowledged that such revelations made his “blood run cold as a parent” — but they also gave him a home-court advantage for having honest, meaningful conversations with his daughter.

“I couldn’t ask her, ‘What were you thinking?!?’ At least, not in the tone in which that is usually said,” Horwitz wrote. “I had to ask her, What were you thinking? In the sense of, What motivated you?”

Horwitz told TODAY Parents that he and his wife Bonnie wanted, above all else, to help their daughter cultivate good decision-making skills before she went off to college — skills Horwitz said he lacked during his own college years.

“We were basically using those last two years of high school as training wheels for college,” Horwitz said. “Our thinking was that when a person is away at college, fear is not going to be an effective motivator.”

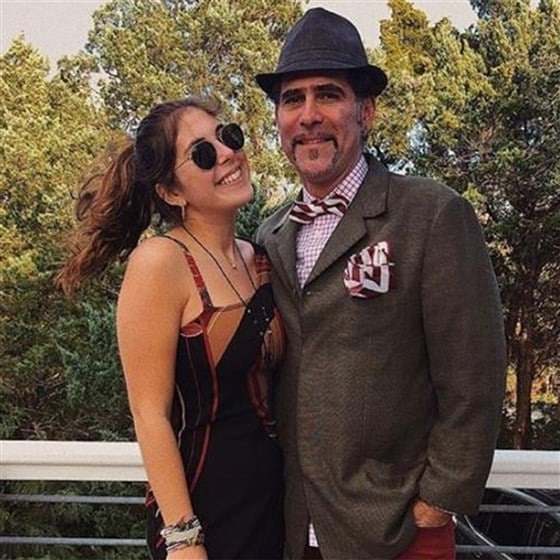

Now a 21-year-old senior at Boston University, Fifer said the lifeline of communication with her parents has made her teens and early 20s so much easier.

“It somehow made me feel like I didn’t need to rebel so hard,” she explained. “I didn’t really need to go crazy. … It was like reverse psychology.”

Child development and parenting expert Dr. Deborah Gilboa said that while Amnesty Day may have worked for the Horwitz family, it might not be the best approach for every family.

“Teens — and their developing brains — need structure,” Gilboa told TODAY Parents. “That includes knowing that there are consequences for their actions, consequences they can’t talk their way out of or be offered a free pass once a month. … There are rarely Amnesty Days in adulthood.”

In Horwitz’s case, the “no punishment” policy was not a “no consequences” policy. Fifer’s confessions didn’t go into a vault, never to be spoken of again. Instead, Horwitz viewed Amensty Day as a personal challenge to discuss what happened with his daughter in a calm, rational way. The goal was to be reasonable and forgiving without shielding Fifer from the consequences of her decisions.

“I’m not abdicating my responsibility to be a parent just because I also want to be a coach at this pivotal moment,” Horwitz said.

For instance, one night Fifer called her dad from a high school party and asked for a ride because she and her girlfriend had been drinking. Horwitz remained stoic when he picked them up — and when one of them threw up in his car.

“I did make her clean out my car the next morning, though,” Horwitz said.

“He did!” Fifer chimed in. “And that night I had been drinking orange juice and vodka, so the next morning they made me drink orange juice. He was still messing with me.”

Fifer said she developed such gratitude for her heart-to-heart talks with her dad in high school that she asked him to write his stories and reflections down so she could have them with her when she went away to college.

“I didn’t know if he was going to do it or if he forgot about it or what,” Fifer said. “But when my parents dropped me off at college, he left it on my pillow. He didn’t say anything about it — I just found it there waiting for me after they left.”

Horwitz is now in the process of revising his love letter to Fifer into a book he plans to call “Amnesty Day: A Father’s Memoir to His Daughter.” The book is due out next year.

Fifer said reading her father’s words helped her stay grounded during her college years.

“I learned in my reading that my parents aren’t perfect, either — they made a lot of mistakes too — so it’s OK if I make some mistakes,” Fifer said. “It’s just a question of how can I improve on them? How can I prevent them in the future? How can I grow?”